Part 1

The new post on Substack: https://apprenticepriest.substack.com/p/the-art-of-paying-attention-314

Part 1

The new post on Substack: https://apprenticepriest.substack.com/p/the-art-of-paying-attention-314

Read it on the Apprentice Priest Substack

https://apprenticepriest.substack.com/p/the-art-of-paying-attention

It started with me a long time ago and it’s still going on.

https://apprenticepriest.substack.com/p/the-priesthood-of-adam-and-the-shape

Follow this link for a new post on Substack: https://open.substack.com/pub/apprenticepriest/p/the-priest-part?r=5axlfw&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web&showWelcomeOnShare=true

Being retired, one has enough time to get into mischief, or in my case, into Substack. This is something thrown together quickly after reading too many Substack posts on the decline of the churches. It’s not that churches aren’t declining. It’s more that the struggles of the institutional church distract us from the deeper reality of Church. (Click below)

It seemed an inauspicious beginning. Last November, in an effort to revive this long dormant blog, I offered a simple post on being an Apprentice of Jesus. That post did not contain a single reference to any spiritual disciplines. The omission was not intentional, but it wasn’t an oversight either. A vague sense of discomfort plagues me when I start to write or teach about spiritual disciplines, rules (or ways) of life, or any of the elements contained in an otherwise welcome renewal of interest in spiritual formation. At least it was vague until I remembered an article by James Bryan Smith written for the September 2022 issue of Christianity Today magazine.. Smith was Dallas Willard’s teaching assistant for his courses at Fuller seminary and worked with Willard and Richard Foster in launching the Renovaré ministry in the late 1980s. Smith’s article was “Dallas Willard’s 3 Fears About the Spiritual Formation Movement.”

According to Smith:

“[Dallas] worried that the focus would be on the practice of the spiritual disciplines themselves rather than on what they were intended to do. Dallas felt this would naturally degenerate into a focus on technique—on the how and not the why of the spiritual exercises. Dallas also feared that churches would co-opt interest in spiritual formation as a tool for church growth—and that, because it likely would not lead to numerical growth, leaders would then relegate formation to one of many departments in a church rather than viewing it as central to their mission. Finally, he was concerned that the growing number of formation ministries would compete with each other—rather than cooperate—in order to validate their work and ensure their survival.”

On the second and third of Dallas Willard’s fears, I may offer some thoughts in a later post. However, the first fear listed raises an important question: what exactly is the “why” of the spiritual exercises? To begin to answer that question, one can look at the consequences focusing primarily on the “how” of the disciplines. Fortunately, Smith address this in another Willard quote:

“In one of our last conversations together, I asked Dallas what would be at stake if his fears became reality. His answer: ‘A lack of transformation into Christlikeness.’”

But is it possible that such transformation is less the goal of the disciplines than it is the effect of seeking that goal? Another of Smith’s recollections give us a hint.

“Dallas taught that disciplines such as prayer, solitude, and Scripture memorization are only one part of the formation process. The second part is the work of the Holy Spirit, and the third is learning how to see life’s trials and events in light of God’s presence and power. One of Dallas’s fears—something he essentially predicted—was that interest in the practice of the disciplines, while essential, would eclipse the other two parts.”

These parts are not three unconnected activities, but three interconnected aspects of the work of apprenticeship. The work of the disciplines is something we do. The way we see our life “in the light of God’s presence and power” is something that grows in us as we become more aware of God’s involvement in our lives. However, the work of the Holy Spirit is God’s sovereign work – which is not to say that we have no part to play in that work. The work we do is in creating space in our lives for the Spirit of God to take up residence and produce the fruit of the Spirit: love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control. Or in other words, the character of Christ.

The disciplines are the essential tool in creating this space. And, oddly enough, preparing to go to sleep is a good analogy for the process. Philosopher Jamie Smith addresses this in his book Imagining the Kingdom. Throughout the book Smith intersperses brief insets under the title of “To Think About.” Drawing on some writing by philosopher Maruice Merleau-Ponty, Smith writes:

I cannot “choose” to fall asleep. The best I can do is choose to put myself in a position that welcomes sleep. I want to go to sleep, and I’ve chosen to climb into bed – but in another sense sleep is not something under my control nor at my beck and call. “I call up the visitation of sleep by initiating the breathing and posture of the sleeper … There is a moment when sleep ‘comes,’ settling on this imitation of itself which I have been offering to it, and I succeed in becoming what I was trying to be.” (Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty, P 189-90, emphasis added.) Sleep is a gift that requires a posture of reception – a kind of active welcome. What if being filled with the Spirit had the same dynamic? What if Christian practices are what Craig Dykstra calls “habitations of the Spirit” precisely because they posture us to be filled and sanctified? What if we need to first adopt a bodily posture in order to become what we are trying to be? (James K.A. Smith. Imagining the Kingdom (Grand Rapids, MI, Baker Academic, 2013), p. 65)

This is an idea and image worth exploring and it raises both further questions and further concerns. The concern that is foremost in my own thinking is the communal context of the Christlike life. Throughout the New Testament the primary context of Jesus’ teaching, and that of Paul and the other New Testament writers, is the corporate nature of discipleship. The “lone ranger” kind of discipleship/apprenticeship is a figment of our western imagination, it cannot be found in the Scriptures.

From that New Testament perspective I can only be a disciple in the context of a community of disciples. I can only be an apprentice in the context of a community of apprentices. This brings to my mind a book by the Rev. Dr. Alison Morgan, Following Jesus. While the book is a valuable tool for any group of apprentices, it is the secondary title that caught my imagination: The Plural of Disciple is Church. If that’s true, and I believe it is, then I come back at last to my revisionist version of Inigo Montoya: “Church! You keep saying that word. I do not think it means what you think it means!”

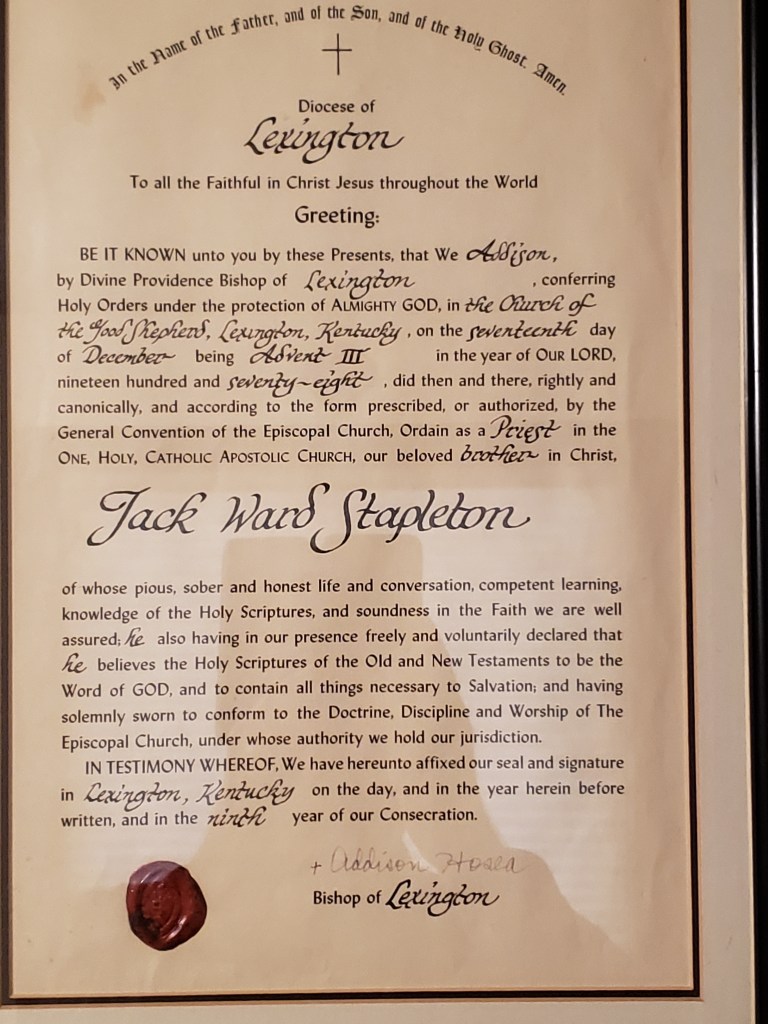

It isn’t my age. In fact, I can barely remember being 46. But it was on this day 46 years ago, in 1978, that I was ordained a priest in the “One, Holy, Catholic, Apostolic Church.” At least that’s what the ordination certificate says.

Although Evergreen, Colorado, has a number of excellent coffee shops and some remarkable brew pubs, I’m not expecting any anniversary discounts today. Being an Episcopal priest is not a particularly notable status in our culture – and it never was as important as we thought it was back in more religious times. That is NOT to say that being a priest is insignificant, only that its significance is not in the arena of national cultural life.

A person ordained a priest maintains two statuses. First is in the Holy Order of priesthood. That status is reflected in three functions: presiding at the Eucharist in the gathered Christian community, pronouncing blessings, and declaring absolution from sin. The second status is the ministry in which the ordained person participates. That can be in parish ministry, institutional chaplaincy, education, or any number of ministries that we can exercise over the years.

The arena in which I exercised Holy Orders has been exclusively the local congregation until I retired at the end of 2018. It was only in the last years of parish ministry that I finally stumbled on a connection between Orders and Ministry that changed the way in which I exercised ministry in the parish. (I have no doubt that many Episcopal priests have been aware of and functioning in that connection for most of their ordained life. I’ve always been a bit slow to catch on.)

The connection is the role of the parish priest in modeling the priesthood that the church members possess in Christ. In short, to teach others to bless, to teach others to pronounce forgiveness of sins, and to teach others to make common things holy (as in Holy Communion) by offering them to the God who transforms and transfigures. That is why this blog is called “The Apprentice Priest.” And that’s what I hope to explore in greater detail in the coming months and (maybe) years.

I would love a day to come when this article, first written eight years ago, would be irrelevant to our times. Unfortunately, that day is not today. The following article was written for the parish newsletter of Trinity Episcopal Church, Greeley, Colorado in 2016. I posted it again in 2020. I thought about updating it then and now, but aside from references to my former parish and the “Trinity Way of Life” it is unfortunately as relevant in 2024 as it was in 2020, and 2016, and every year in between.

So who in the world is Fursey? He’s a rather obscure Irishman who gets a mention in Bede’s History of the English Church and People. I read that book in seminary and for something written in 731 AD it’s quite readable. Bede mentions quite a few Irishmen for a book devoted to the development of Anglo-Saxon England. Each year I get a reminder of Fursey for a week during the second week of Advent in the prayers Dorie Ann and I use at the lighting of our Advent wreath at home. One section of the devotional tells of a vision of “four fires through which unclean spirits threatened to destroy the earth.” They are listed as the destroying fire of falseness, the destroying fire of greed, the destroying fire of disunity and the destroying fire of manipulation. And each year, but particularly this one, we comment on how contemporary this feels.

Fortunately, the devotional doesn’t end there. It continues: But Fursey urged everyone he met to do as the angels told him: to fight against all evils. He encouraged them with these words he had heard: “The saints shall advance from one virtue to another;” and, “The God of gods shall be seen in our midst.”

At first the encouragement Fursey offers seems pretty pale against a set of destroying fires. In a world that seems beset by falseness, greed, disunity and manipulation we might be excused for wanting stronger stuff that what is on offer. Yet implied in these messages from the angels is a charge to follow the Jesus path as the means by which God overcomes the destroying fires.

The first charge is to fight against all evils. The first all too human reaction is to take up arms, whether political, economic or military, meeting might with might to set things right. This is not the Jesus path. If we fight fire with fire, fire always wins. There are other ways to fight against evil than to use the tools of evil. Paul enjoins the Roman Christians to follow the Jesus path in these words: “Do not be overcome by evil but overcome evil with good” (Romans 12:21) To confront evil with good seems anti-intuitive to us, but only because the Jesus path is not the path that we were taught either by the world around us or even, sadly, by the church much of the time.

To fight against all evils means that wherever we find cursing in word or action we respond by blessing in word and action not only the victim but even the perpetrator. In the orbit of our reach, no evil done to others is irrelevant to us. We are God’s agent of blessing and that is our first duty.

The next word to Fursey from the angels is that “the saints will advance from one virtue to another.” We dare not turn this into an inward concern about building our own character. Virtue has substance only in so far as it is demonstrated by word and action in our relations with others. Advancing from one virtue to another means that our growth in Christ and therefore in virtue is a continuous journey. The primary function of a spiritual discipline, whether the Trinity Way of Life* or any other set of disciplines is to keep and guide us on that journey. Therefore, it is never enough to simply come to worship, listen to teaching, receive nourishment in the Sacrament and then drop back to spiritual passivity for the remains of the week. What we receive we are to apply through the tools of our spiritual disciplines until we rejoin the worshiping community the following Sunday to build one another up, to share the stories of what God has done, accept the divine strength given in Holy Communion and return to the fray growing in the good works God is preparing for us.

The final word from the angels is that the God of gods shall be seen in our midst. In late November we began a preparation for Christmas in Advent and we are just now completing the 12 days of Christmastide. The birth of Jesus is the story of the God of Israel joining Israel in the midst of Israel. The God of gods is seen in their midst even though many do not recognize him. John’s Gospel notes that “He came to that which was his own, but his own did not receive him. Yet to all who did receive him, to those who believed in his name, he gave the right to become children of God– children born not of natural descent, nor of human decision or a husband’s will, but born of God.” (John 1:11-13) This adoption by God in Jesus is done through our baptism and its significance extends far beyond our personal salvation.

It cannot be said often enough that Christmas is not the end of the story of God’s redeeming work but its beginning. Jesus’ life, works and words covered a period of 33 years. The culmination of those years was traumatic and dramatic. But even that was not the end of the story. In fact, the Jesus story is still going on, acted out by generation of generation of apprentices of Jesus. The God of Israel entered Israel but now moves beyond the community of Israel into the gentile world. Wherever we are faithful, the God of gods is seen in our midst.

This past year has been a difficult and painful year all over the world and also in our local community. There seems to be an encroaching darkness that fills millions and even billions of people with anxiety and fear. But as John the evangelist also notes: “In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” (John 1:4-5) In 2017 the challenge to the community at Trinity (and to Christian communities everywhere) is to be bearers of that light. In times of anxiety and fear we have a mission to carry out. If we take that mission seriously and execute it prayerfully and faithfully the destroying fires of falseness, greed, disunity and manipulation will never have their way.

*As of 2018 the Trinity Way of Life included Pay Attention (prayer), Show Up (community), Serve Others (service), Learn the Story (study), Give as you receive (generosity), Check In (accountability), Practice Gratitude (thankfulness), and Tell the story (witness).