In the case of Simon the Magician, we have a story of a new convert who has just begun the journey of conversion. Unless, of course, conversion is a complete event rather than the beginning of a process. In which case the story of Simon is that of a false conversion. Conversion as a complete event, however, raises troubling questions about the disconnect between how Christians live and how they are expected to live according to the Scriptures. It also raises troubling questions about the behavior of Christian congregations particularly in light of those who have suffered abuse in churches. The example of the Corinthian church used in the previous post can be either a sign of the falsity of Christian claims or, if conversion is treated as an inauguration, a warning that the conversion journey is long and difficult.

But there is another Scriptural example of incomplete conversion that does not involve a person outside the covenant community like Simon, or a congregation like the Corinthians who bring a great deal of pagan baggage into their new life. Instead this is a group that has been on the “inside” of the Jesus Movement and whose lives, prior to connecting with Jesus were steeped in the Torah, the prophets, and the writings. This group is known to us as the Apostles.

The four Gospels offer us several incidents where they just didn’t seem to be able to hear Jesus. There are two in the Gospels and one at the opening of the Acts of the Apostles that illustrate the problem. In Matthew’s version of the confession of Peter we have the intense moment of Peter’s response to Jesus’ question: “Who do you say that I am?” is “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” Jesus in turn blesses Peter and declares him to be the Rock, and gives the keys to the kingdom of Heaven. But then Jesus goes on to teach them about his fate: betrayal, suffering and death. Peter takes Jesus aside and rebukes him for such an expectation insists that such a thing could never happen. To this, Jesus responds: “Get behind me, Satan! You are a hindrance to me; for you are not on the side of God, but of men.” (Mathew 16:23) From hero to zero in two paragraphs is a pretty spectacular fall.

The second incident is in two parts in Mark’s Gospel. Jesus is heading towards Jerusalem for his final confrontation. The first is an awkward moment when they reach Capernaum: And they came to Capernaum; and when he was in the house he asked them, “What were you discussing on the way?” But they were silent; for on the way they had discussed with one another who was the greatest. And he sat down and called the twelve; and he said to them, “If any one would be first, he must be last of all and servant of all.” And he took a child, and put him in the midst of them; and taking him in his arms, he said to them, “Whoever receives one such child in my name receives me; and whoever receives me, receives not me but him who sent me.” (Mark 9:33-37)

Jesus’ use of a child to illustrate doesn’t seem to make much of an impact as shortly thereafter he has to rebuke his disciples for trying to send children away (Mark 10:13-16). But the real problem occurs later in the chapter when James and John ask Jesus to grant them the chief positions in his glory. The other disciples are indignant, perhaps because the Zebedee brothers beat them to the mark. Jesus again tries to teach them that his kingdom operates by different rules: And Jesus called them to him and said to them, “You know that those who are supposed to rule over the Gentiles lord it over them, and their great men exercise authority over them. But it shall not be so among you; but whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be slave of all. For the Son of man also came not to be served but to serve, and to give his life as a ransom for many.” (Mark 10:42-45)

It is easy to portray Jesus’ disciples as hopeless clods who (in the wonderful phrase of Dorothy Sayers) “couldn’t find a herd of black elephants on a snowbound field in broad noonday.” That is not only untrue and unfair, it misses a critical point about both the disciples and about conversion. While the beliefs and expectations about the messiah were not uniform among the Jews of that time, there was a popular hope for one who would deliver them from Roman bondage, purify the Temple and reestablish the Davidic kingdom. Behind these hopes was a set of unspoken assumptions that this deliverance would come about through the military overthrow of Rome and the normal uses of political power energized by powerful acts of Israel’s God.

The acts of power performed through Jesus were signs of hope as was his preaching on the kingdom, on integrity in observing the Torah and his rebukes of the Temple authorities and the religious establishment. When Jesus starts teaching that he will be betrayed and executed, there is no conceptual box in the disciples’ minds to place such a thought. The jockeying for positions in Jesus’ coming kingdom is normal operating procedure and, again, his insistence that the path to leadership in his kingdom is through humility and service finds no place in the disciples’ world view.

And therein lies the problem. We are rarely conscious that we even have a “world view” much less aware that there are other alternatives. This is why the incomplete conversion of disciples is sometimes the most difficult to discern. We may be raised in church community and even in a family that seeks to apply their faith to their daily life, work, and relationships. But we are also raised in a cultural locality, region, and nation. Whether we are raised in America or Armenia or Austria or Australia, whether in Germany or Ghana or Guyana we have a view of the world that is both pervasive and yet, for the most part, invisible to ourselves.

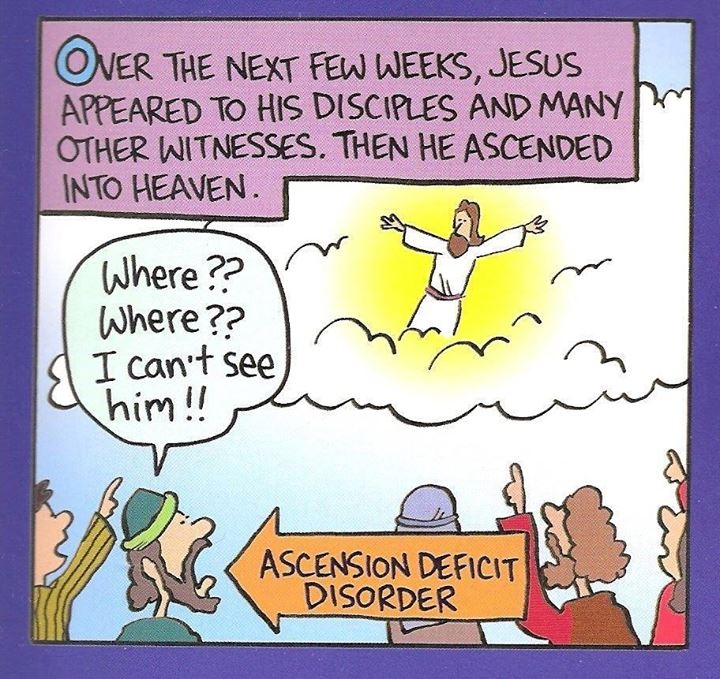

The disciples, bound by their world view, simply could not register what Jesus was telling them. They went through the trauma of Jesus’ betrayal both by Judas and by the Temple authorities. They saw him arrested, tortured, and crucified. And then they experienced the wonder of his Resurrection. And still, as Acts records, when they accompany him to the place of his Ascension, the question foremost in their minds is “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” (Acts 1:6)

They weren’t dumb. Yet they were blind. And their conversion needed to go on. As does ours.